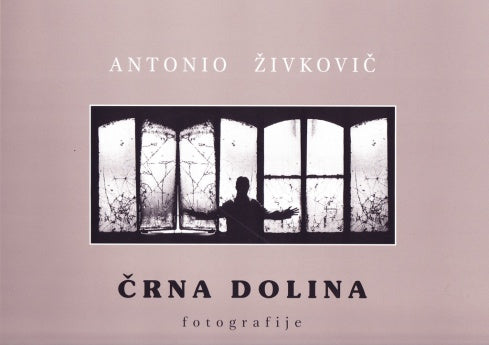

Antonio Živkovič / Black Valley

Antonio Živkovič / Black Valley

Couldn't load pickup availability

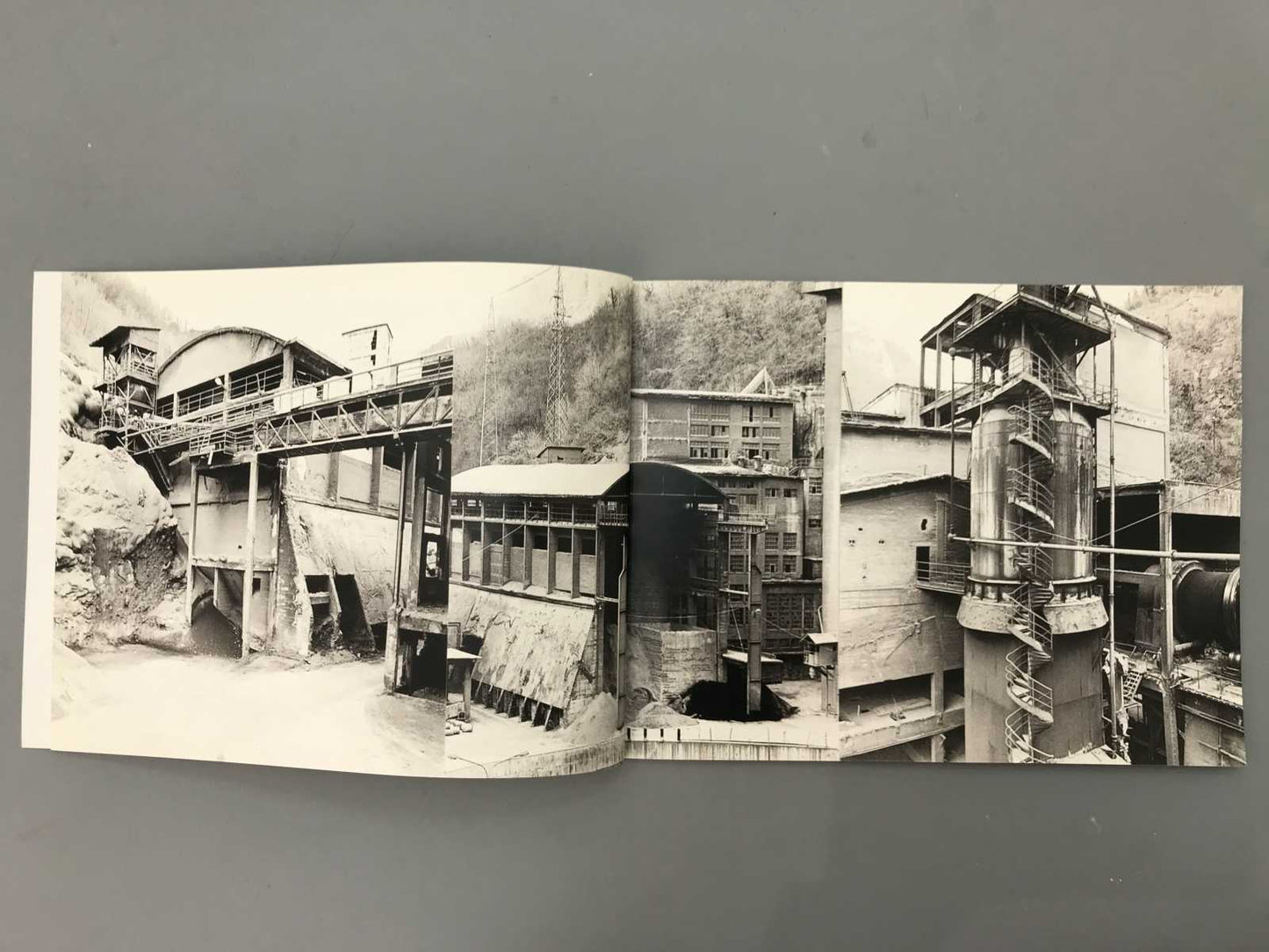

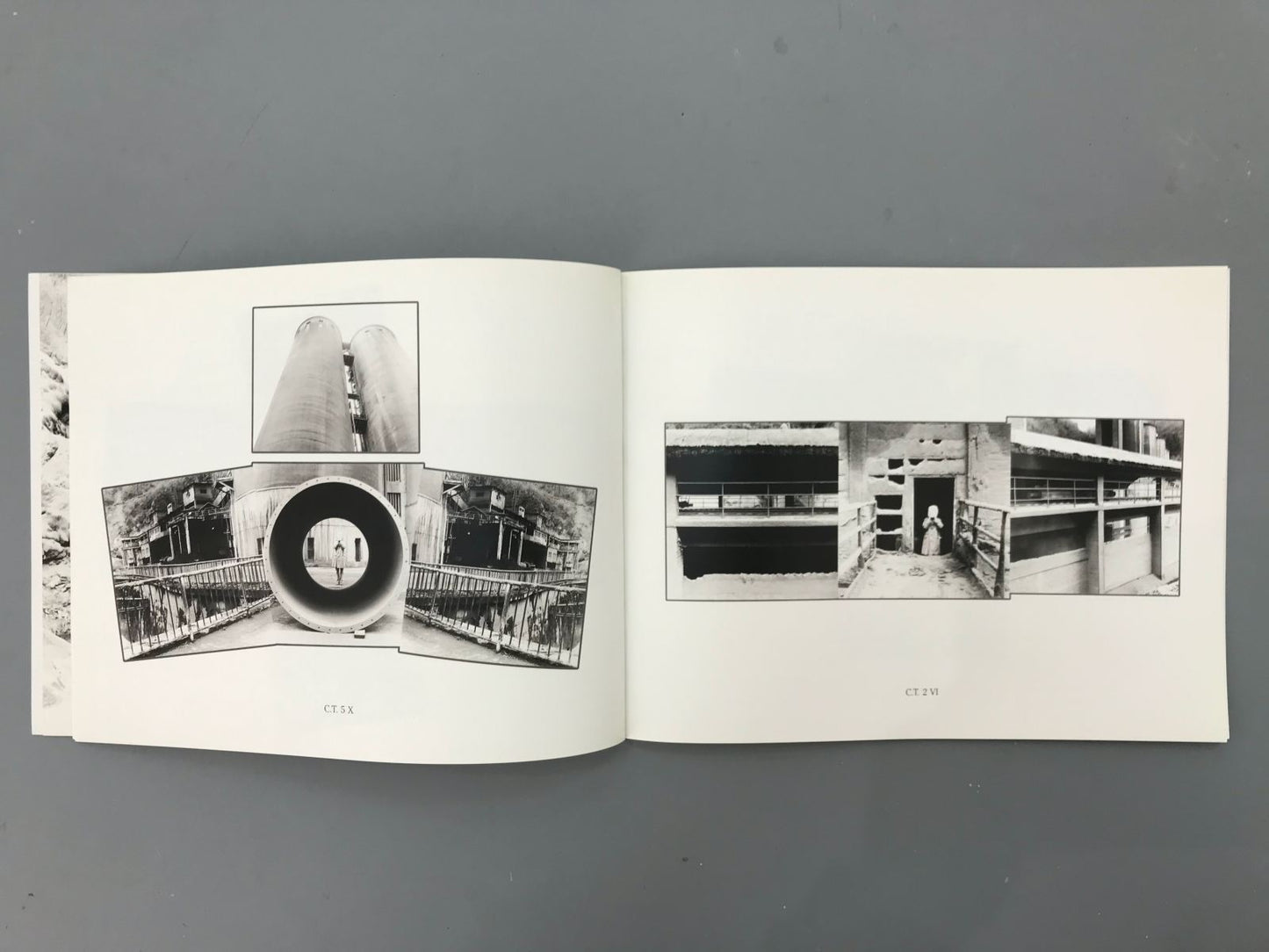

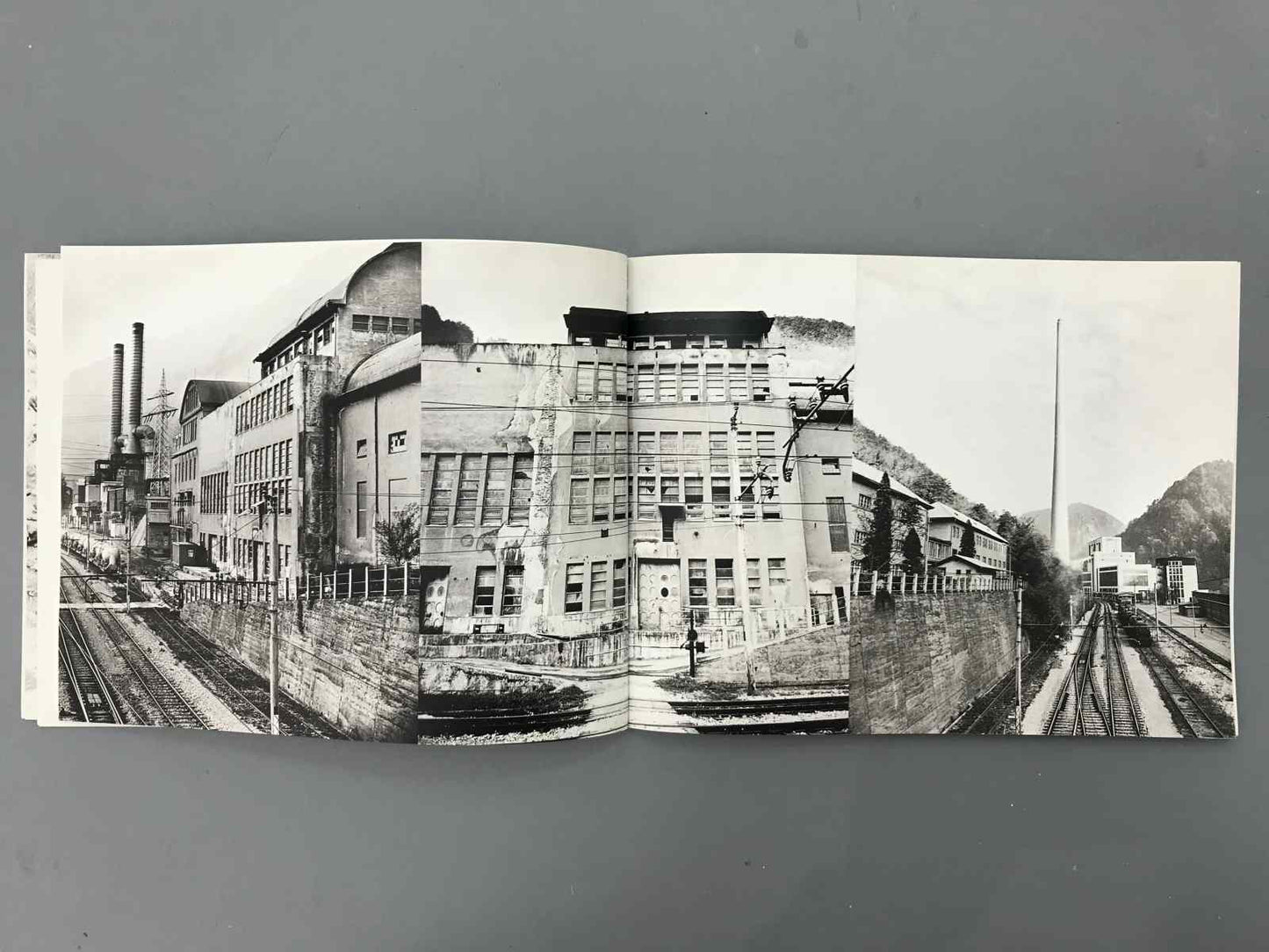

Things and images, behind their appearance, always hide another reality, which can be more hell- or heaven-like than we are willing to believe or admit. In brief - they may significantly surpass our reveries and expectations. I always remember this when I tell somebody of my place of birth; or - in this case - of the domicile of these photographs and the man who took them, Antonio Živkovič - Trbovlje. The very mention of Trbovlje usually incites in the interlocutor a feeling of nausea, horror and last but not least, sympathy. People always associate Trbovlje with the lower part of town, the entry into the valley, the bottle-neck guarded by the chimneys of the cement factory and the power plant, which they might have seen while passing through the area. And these lower parts, if I try to express myself in another language, represent the antechamber of hell. Any man who has experienced this part of Trbovlje with his eyes, and perhaps his lungs, is fully entitled to prejudice and the above-mentioned reactions. Perhaps, on seeing Trbovlje or hearing it mentioned, certain drawers open up in his or her mind, the compartments storing half-forgotten history classes, or perhaps Slovene classes, the chapters about Rdeči revirji. About the core of rebellion and permanent smoldering similar to that going on in the boilers or the cauldrons of hell emanating a constant stench of sulphur. Or perhaps he or she is reminded of the early phases of capitalism, the position of the working class, the low wages, Zola's Germinal, the mining trolleys - cicke and hunte - dragged along the mines by children and blinkered horses. Or, if I try to move from the late 19th century to the present, the late 20th, one may be reminded of apocalyptic visions, of the end-of-millennium nightmare about the advent of antichrist, of the end of industrial civilisation. If the interlocutor's memory is sharper and more accurate, he or she might remember the Orjuna and the first socialist strike taking place

in 1956. The glue that holds together all the associations, those related to the past and to the present, transcending the thoughts of an observer, is work. Above all the depersonalised process of work symbolised by the person in the photos, the person with a stone face. In Trbovlje as well as in other industrial towns, work has always been analogous with hardship, never with pleasure. This heritage has been instilled in us through stories, reputation, tradition, and above all the social lyrics. Those of us coming from Trbovlje are supposed to bear this tradition like a seal, like a birth-mark. This heritage and the impression related to it have lived in stories alone, only in the appearance of things, and never in their other reality. Trbovlje is far from being the antechamber of hell or purgatory: it resembles heaven instead. And this is why I, as an insider, in the photographic trilogies of Antonio Zivkovič primarily perceive the other reality. The images of neglect and the attributes of industrial civilization, the pictures of the core of the first five-year plan reveal to me something else, a time which has entered the memory. And which can only be reached through dreams or art. I can see Trbovlje as the destination of all expeditions, as the constant flow of light, a Trbovlje which to us seemed endlessly vast and limitless. A Trbovlje without the feeling of claustrophobia, a Trbovlje existing in the sky of our childhood. A Trbovlje one cannot imagine featuring in the title of a novel - A Black Valley - but rather in another title - How Green Was My Valley. And this strong and clear vision is ensured by Živkovič's photographs, with great persuasion reminding me of the verse I recently came across. I do not remember the name of the poet. The verse goes something like this: Whoever has not smeared himself with mud / Cannot hope to reach the sky. - Uroš Zupan

Language: Slovenian, English

Size 24 x 31 cm

Binding: Softback

Publisher: Self-published, 1999